Danbong – Short Stick

Descended from an Ancient Musical Device,

It is Now a Signature Weapon of Hwa Rang Do

(Black Belt Magazine – March, 2003)

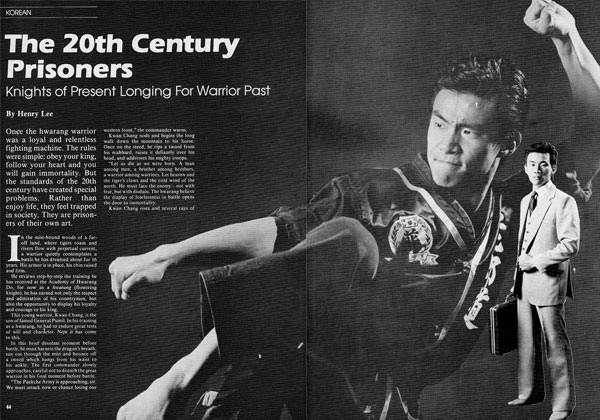

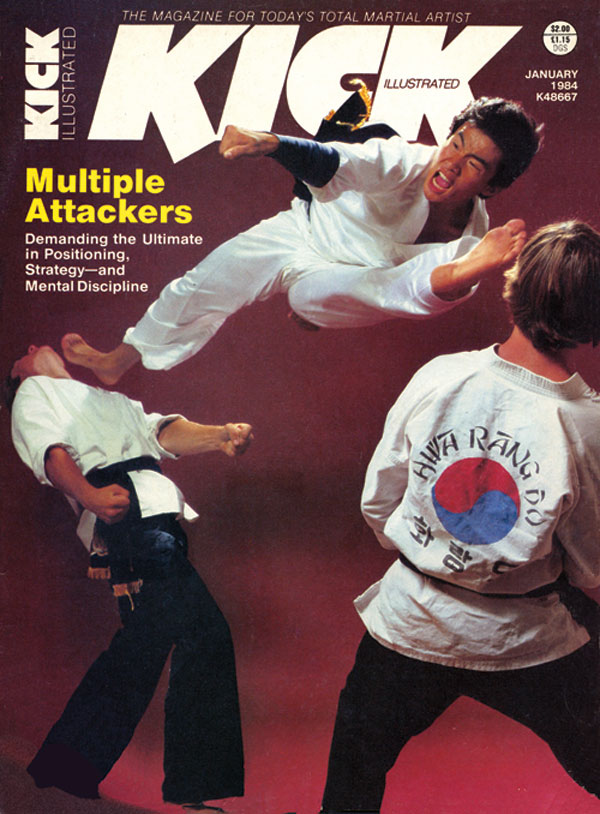

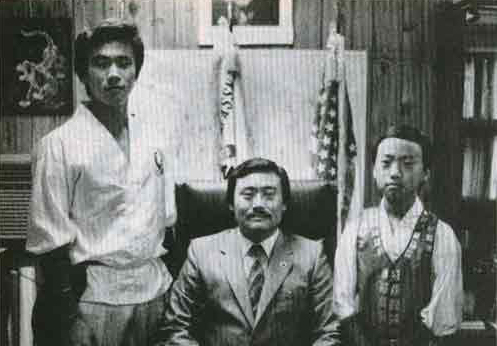

At first glance, the short stick appears to be one of the most innocuous parts of the hwa rang do arsenal. Measuring only about a foot long, it carries none of the visual shock value that a baseball bat or even a carpenter’s hammer would have in a dark alley. It’s not made of any exotic materials, and it’s not wielded with any kind of flashy movements. However, when it’s used right, the short stick is rudely effective. Perhaps that’s why I figures so prominently on the crest of Joo Bang Lee’s World Hwa Rang Do Association, the group responsible for bringing the comprehensive Korean self-defense art to America and the world.

History

The dan bong, as it’s called in Korean, descended from the drumsticks that Buddhist monks used-and still use-to beat the large drums that sit in every temple in the nation. In olden days, the priests would pound the instruments for prayer services and during emergencies when an alarm needed to be sounded in the monastery.

Use of the drumstick for self-defense became popular in the secular world during Korea’s Koryo dynasty, which lasted from 935 to 1392. “Policemen who were weaker and couldn’t rely on sheer physical force to overcome criminals used it as a tool to subdue their opponents,” Lee says.

The effectiveness of the weapon enabled those early law-enforcement officers to neutralize any advantages the hoodlums had without inflicting mortal injuries. And its small size meant it could be easily concealed or stowed when necessary.

Construction

Then and now, the typical dan bong was a cylindrical piece of wood approximately 1 inch in diameter and 10 to 12 inches in length. A hole was bored in one end to allow the attachment of a tether, which could be wrapped around the martial artist’s hand and thumb to ensure a more secure grip.

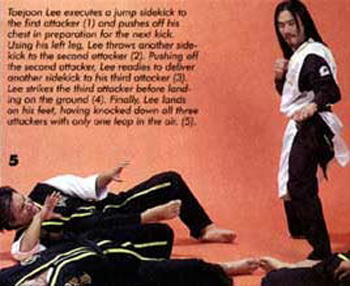

Lee’s elder son, Taejoon Lee, himself a seventh-degree black sash in hwa rang do, extrapolates on the short stick’s structural practicality: “Most of the uninitiated view the dan bong as a joke. They squint and see this small wooden thing barely jutting out of the palm of your hand, and they laugh.”

Indeed, the dan bong in nondescript and can be partially concealed in the palm, but that only helps the bearer swing it into action with the element of surprise on his side. And as hwa rang do practitioners love to demonstrate, the simplest item or movement can have the greatest potential in combat.

Application

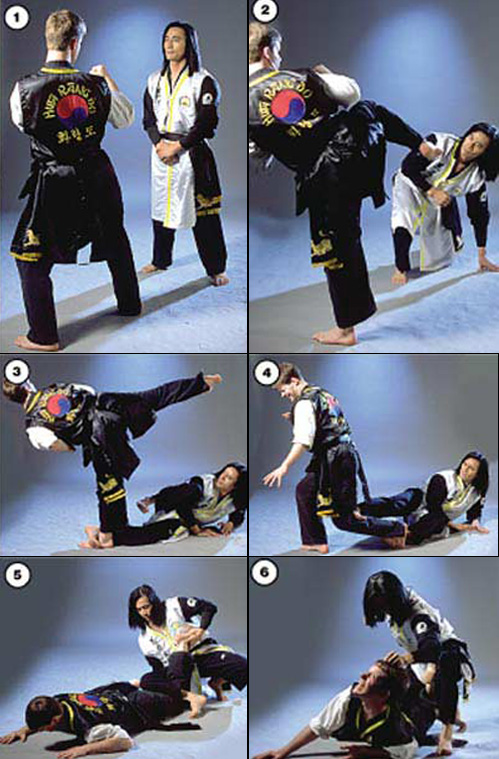

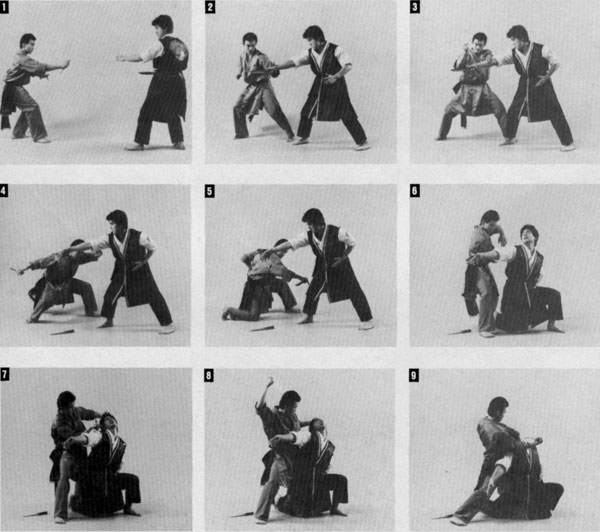

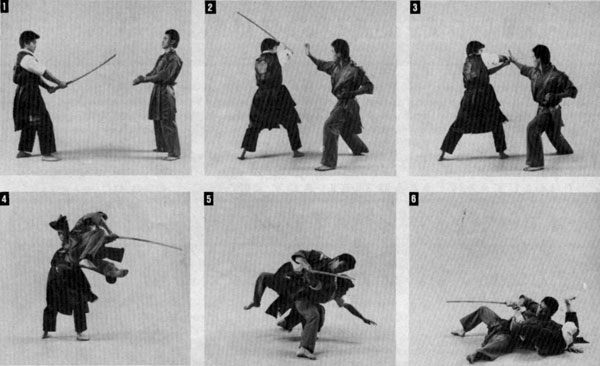

According to Taejoon Lee, the simple structure of the dan bong conceals five major fighting tools: the edge, the forward tip, the shaft, the pommel and the tether. In battle, those features can be applied in a number of devastating ways-which is in accord with hwa rang do’s concept of applied combat versatility, meaning that the maximum number of effective applications must be derived from every weapon and body part.

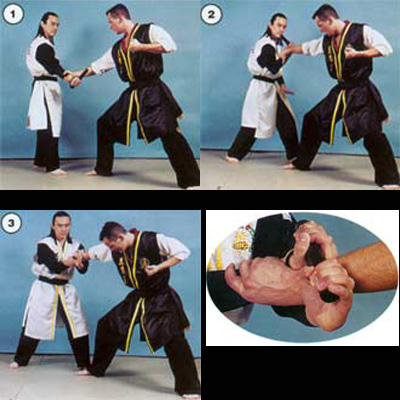

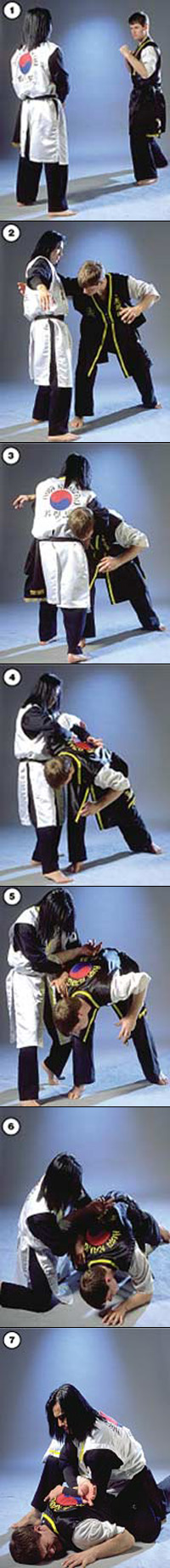

The edge of the stick, especially when not smoothed or rounded, provides an angular surface that is not dissimilar to the blade of a knife. It can be used to gouge, cut into or scrape off an adversary’s skin. Further versatility comes from the fact that one edge lies at each end of the weapon. If an opponent deflects a dan bong head strike, a simple twist of the wrist can enable you to redirect the edge so it makes contact with his face, injuring him and leaving him open to a follow-up strike.

The forward tip of the short stick is employed much like the tip of a hammer-using thrusting, stabbing and hacking motions. Additionally, the sides of the forward tip can be used with a flicking action of the wrist. Taejoon Lee explains: “You hold the dan bong loosely between your thumb and forefinger, and power it with the rolling action of your fingers. That allows rapid alternation between pronating and supinating your wrist, making the forward tip much like a heavy whip.”

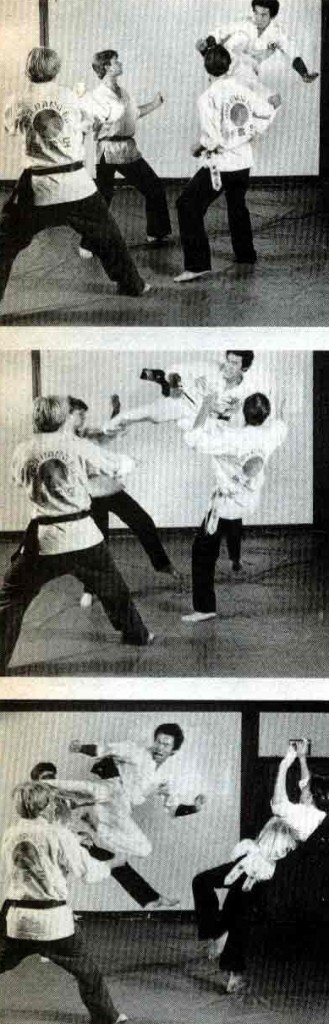

When it comes crashing down on a joint or other hard body part, the bone underneath will shatter. That kind of whipping motion is clearly seen in hwa rang do’s dan bong blocks and strikes, making defense potentially as painful as offense. Indeed, Joo Bang Lee is fond of demonstrating the myriad of uses to which the short stick can be put by answering an opponent’s kick with a flicking tap to the shin. The adversary’s face inevitably turns white with pain after the seemingly effortless strike makes contact.

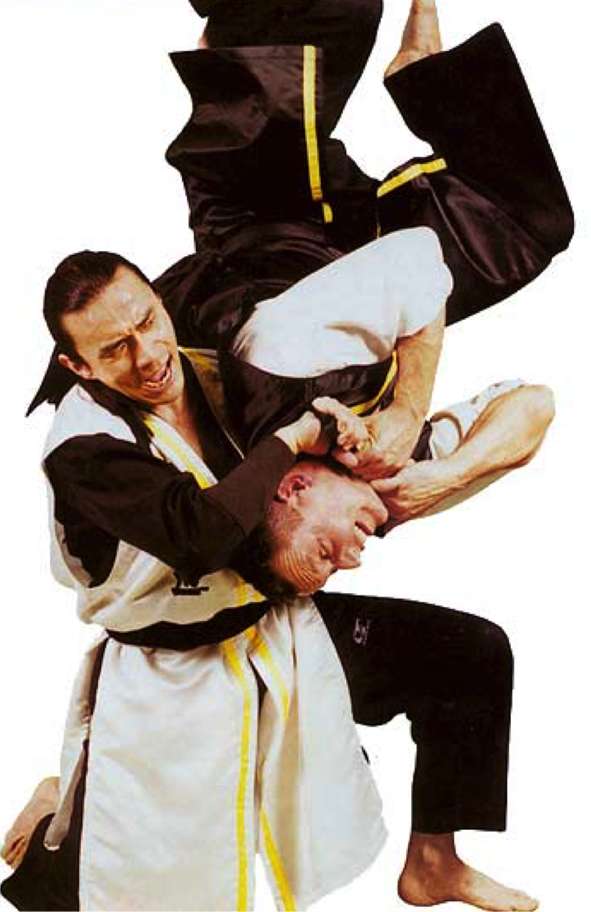

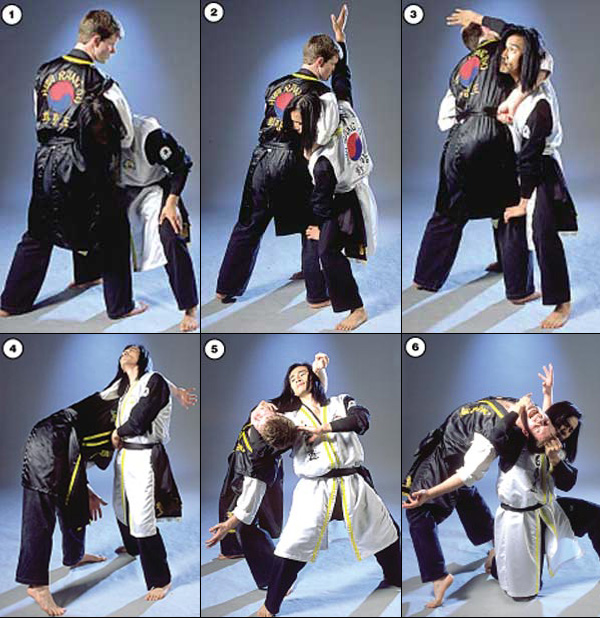

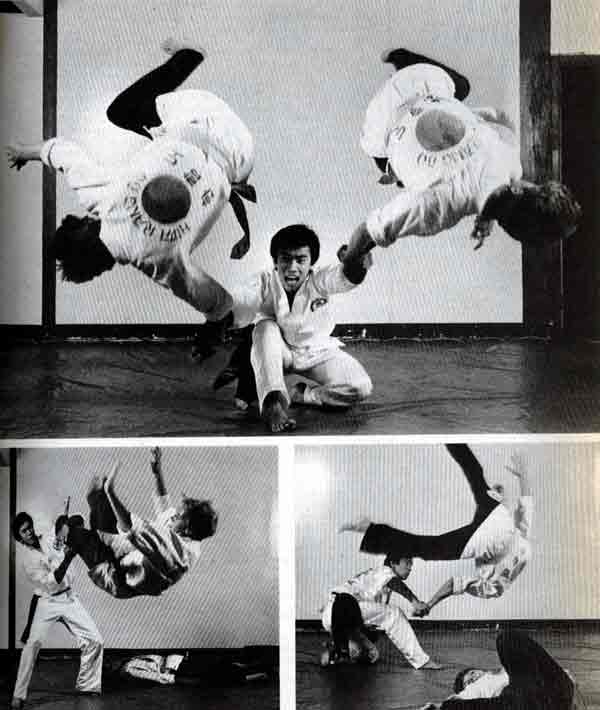

The dan bong’s shaft exemplifies versatility. While most arts teach students to use the body of an impact weapon only for blocking and striking, hwa rang do does not encumber its practitioners n any way. “The shaft of the dan bong can be used as an additional appendage,” says Joo Bang Lee. To demonstrate his point, he blocks a punch to the face, then deftly flips the shaft over his opponent’s wrist and grabs the tip with his free hand. The slightest downward force drops the opponent in a screaming heap. Lee then points out that joint manipulations are an essential part of combat and that the short stick’s rigidity makes it the perfect tool for creating additional force on the targeted joint or pressure point. Additionally, he says, the shaft serves to stabilize the fingers in a fist, much like a roll of quarters that is held wile a punch is thrown.

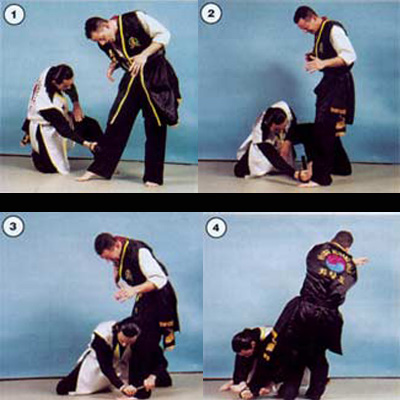

The short stick’s pommel can function as an excellent striking implement. When the forward tip is blocked, the pommel can whip around and hammer home a punishing strike-to the collarbone for instance. In close-range fighting, the pommel is often used as a shorter tool for augmenting the power of a joint manipulation. “Many times, someone will grab your weapon arm,” says Joo Bang Lee. “If that occurs, you don’t have to forgo a joint-manipulation technique simply because one of your hands is occupied with a weapon.” In such a situation, the pommel of the stick can easily circle the opponent’s wrist to effect a lock, and the lock can be more painful than an empty-hand lock because it uses the wooden surface to simultaneously pinch down on the pressure points in the wrist.

The dan bong’s tether is actually an important offensive tool, despite the fact that most observers see it as merely an apparatus to keep the stick from flying out of your hand. It can also be used to assist you in restraining an opponent’s wrist during a lock or in choking him afterward. Additional utility comes from being able to use the tether to create a flexible weapon: You grasp it while you strategically fling the dan bong into your opponent’s face, then yank it back into your palm. The skilled practitioner also knows how to link two short sticks together to create a makeshift nunchaku.

Extrapolation

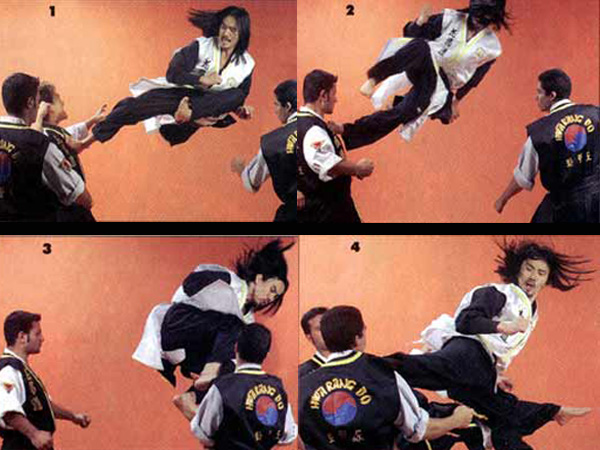

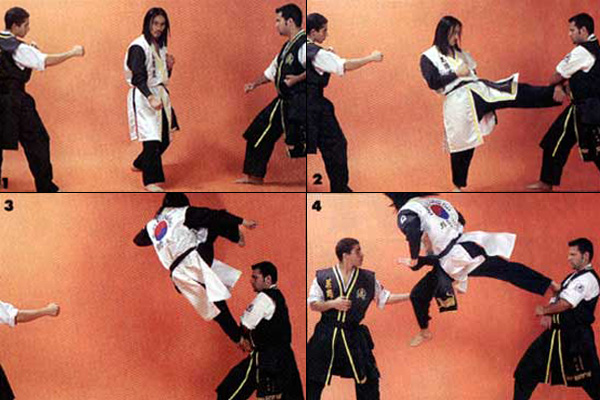

Martial artists tend to think of wooden weapons primarily as impact devices, but the hwa rang do short stick is obviously different because it enables you to strike, cut, lock and throw. “That gives you the full gamut of fighting techniques so you’re not limited to just beating wildly on someone like a child with a stick,” Taejoon Lee says. “The problem for many people lies in failing to achieve an adequate understanding of basic empty-hand combat, which can make bearing a weapon a detriment.”

If you decide to train in the use of the short stick-or any other hwa rang do short-range weapon-you must learn how to use both hands in a coordinated fashion, blocking and striking in a figure-8 or circular pattern, Taejoon Lee says. “Maximum damage is the goal of both empty-hand and weapons [techniques], so a solid understanding of pressure-point striking is also necessary.”

When it comes to self-defense, the most important thing to remember is that dan bong techniques can be done with a plethora of household items. Whatever is handy-be it a coke bottle, wrench, cell phone, flashlight or TV remote control-can be wielded with the same authority.

“As long as it is semi-cylindrical and fits in your hand, it will have most of the [features] mentioned above and can be applied with dan bong principles,” Taejoon Lee explains. “While hwa rang do teaches the use of some ancient Korean weapons, it is all applicable to modern life and modern conflict.”