By Mark Cheng

Photos by Rick Hustead

In the self-defense world, the hot topic is mixed martial arts. In this eclectic arena, almost anything goes when it comes to techniques. The nonstop action has drawn in a whole new generation of competitors and spectators. Long before TV cameramen pointed their lenses on the octagonal ring, however, an art of countless possibilities and similar guiding principles bloomed on Korean soil.

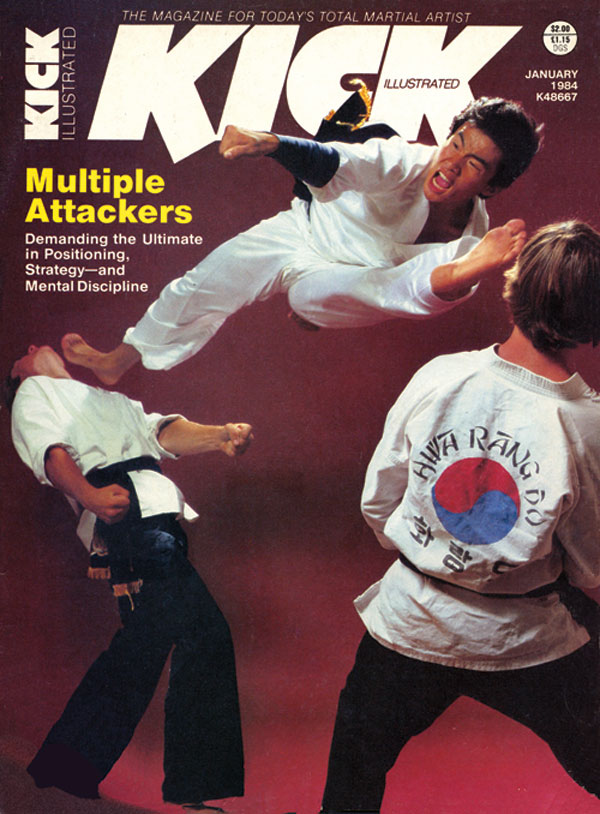

Born out of the martial and medical kingdom of Korea’s ancient Hwarang Knighthood and organized into a modern system by Black Belt Hall of Fame Member Dr. Joo Bang Lee in the mid-20th century, Hwa Rang Do encompasses the entire gamut of combat techniques. While other arts showcase their power primarily from punches and kicks, Hwa Rang Do practitioners soar through the air with whirlwind hand and foot strikes, as well as grounded locks, throws and grappling moves that demonstrate the utmost finesse.

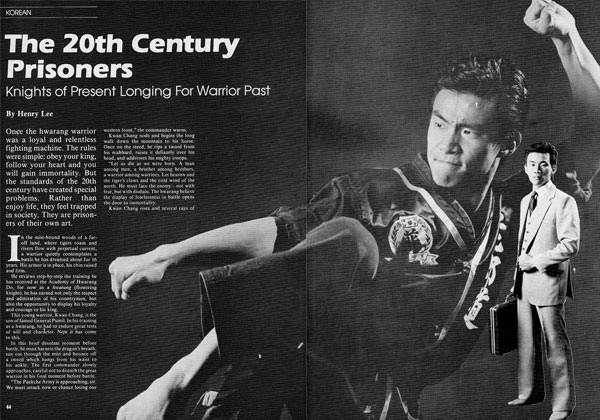

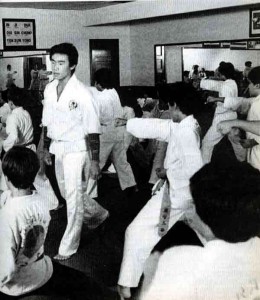

Taejoon Lee, the eldest of Joo Bang Lee’s children and heir-apparent to the system, sheds light on the historical evolution of the art: “When Hwa Rang Do first came to the United States, everyone wanted to learn how to punch and kick. The flashier moves brought in more students, and my father adjusted the curriculum and ranking system from his original Korean teaching structure to fit our new home.”

“Back then, grappling wasn’t very popular,” he continues. “People who were interested in martial arts wanted effective techniques that looked good, too. With a kick, you can generally get an idea of its power without having to feel it, but a submission technique requires experience for you to appreciate it. Ground grappling, by and large, isn’t as visually exciting as percussive techniques are. Just look at the way the rules have changed in the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Because spectators demanded more visual excitement, the promoters restart the fights [in a] standing position if there’s too little action on the ground.”

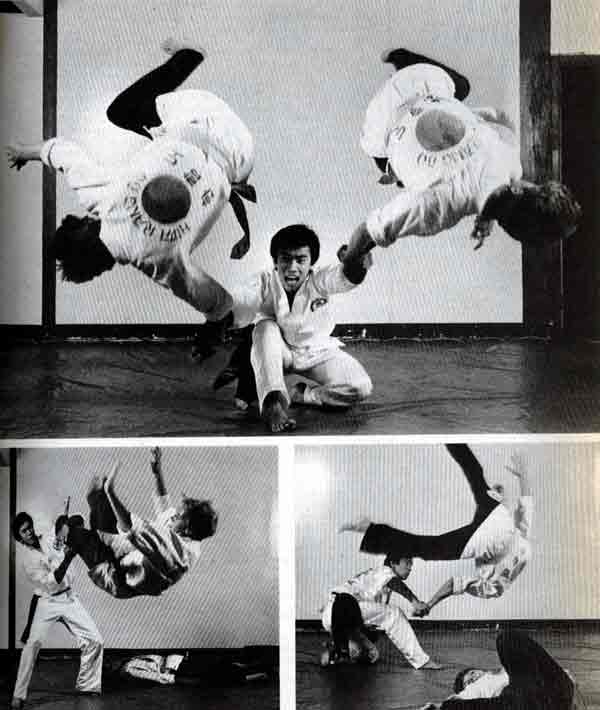

Viewing footage of Hwa Rang Do training and demonstrations held in Korea during the 1960s, it’s easy to see that Joo Bang Lee was right on the money. Between demonstrations of their breaking and weapon prowess, practitioners can be seen performing a plethora of joint manipulations, throws, takedowns, ground-grappling moves and submission techniques.

Continuing with his father’s mission to make Hwa Rang Do a viable and well-rounded system that meets the needs of its environment, Taejoon Lee has developed a new system for training students to survive non-lethal encounters – which, no matter what some might argue, make up the majority of self-defense situations. The three-step process combines the joint manipulations, takedowns and throws of Hwa Rang Do into a defend-takedown-submit format that’s an effective alternative to knockdown-and-drag-out combat.

Three-Part Plan

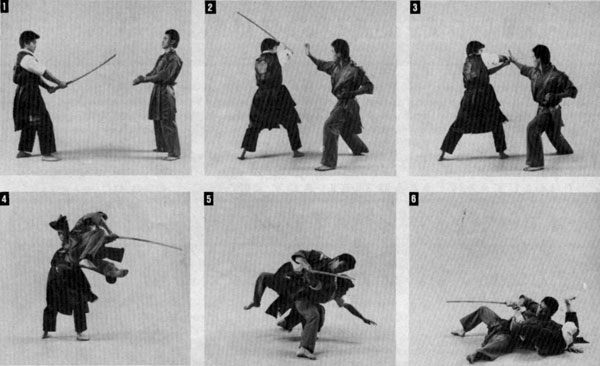

One truth of combat is that the more techniques there are in a combination, the less likely it is that your opponent will move the way you’ve planned. To deal with that, Lee divides his lesson plan into stages. Stage I deals with encounters that happen in a standing position at long range – where kicks and punches dominate. The primary objective is to close the gap safely while nullifying the attacker’s technique.

Stage II addresses close-range combat, where the transition from standing to the ground occurs. The objective centers on the execution of joint manipulations, pressure-point techniques, takedowns and strikes with the elbows, knees and forehead. This stage ends with the opponent on the ground in a nondominant position.

Stage III is divided into two parts. Stage IIIa is the one-knee position. It applies when you’re on one knee and your opponent is supine or prone. The goal is to finish the fight using joint-lock dislocations or submissions without rolling on the ground with him. This stage is vital in street-survival, law-enforcement and military applications in which grappling with a single adversary can reduce your ability to fend off multiple threats and, if you’re armed, to maintain control of your weapon.

Stage III itself occurs when you and your opponent are on the ground. It’s the last and least favorable option, one in which you must submit him or finish him. The emphasis on learning how to control him utilizing grappling and submission techniques.

For each Stage I attack, Lee covers the bases with different Stage II and Stage III options, depending on the positioning and reaction of the opponent. The beauty of the system is that it contains techniques that range from simple to athletic, so there are options for every skill and fitness level. A snapshot of this revolutionary fighting method can be seen in the classic two-hand C-lock.

The Fundamentals

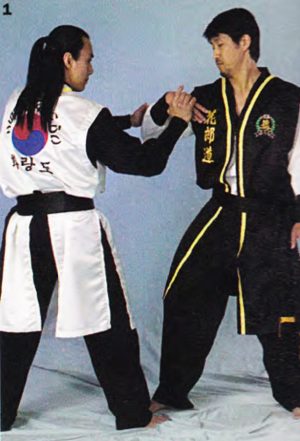

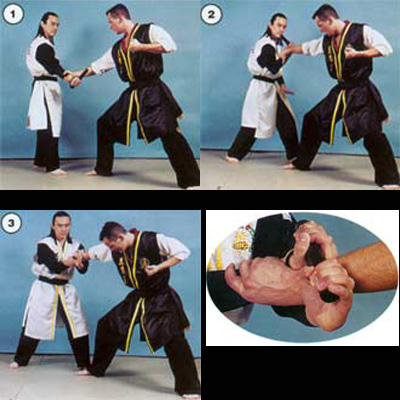

The basic C-lock is one of the most widely used wrist-manipulation techniques in the martial arts. It’s effected by placing your opponent’s wrist and elbow at a 90-degree angle with his forearm, forming a rough C shape. While there are many ways to enter into this technique, the most important component is establishing control over the opponent’s hand so you can create the proper angle on the wrist.

The two-hand C-lock is essentially the same as the C-lock, but with a modified hand position. One of your hands is placed on your opponent’s hand near his wrist, while the other controls his elbow. The additional elbow control increases the strain on his shoulder, which can be dislocated by a little extra vibrating pressure. While the technique differs from a figure-4 application, it places similar stress on the joints and can be used to enter into the figure-4. The two-hand C-lock requires solid control over the opponent’s hand, forcing it into a C shape with his arm.

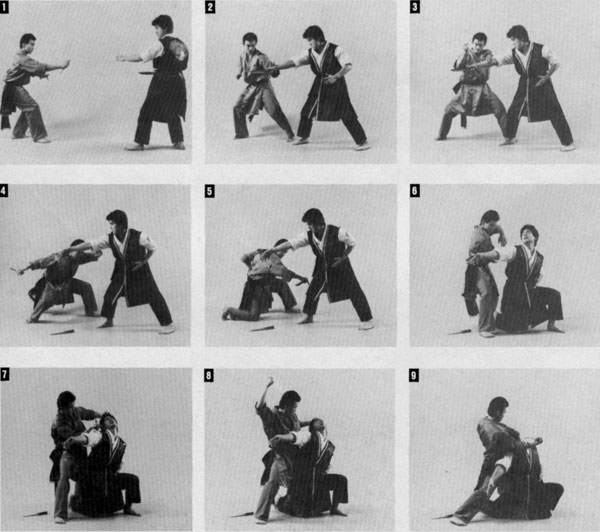

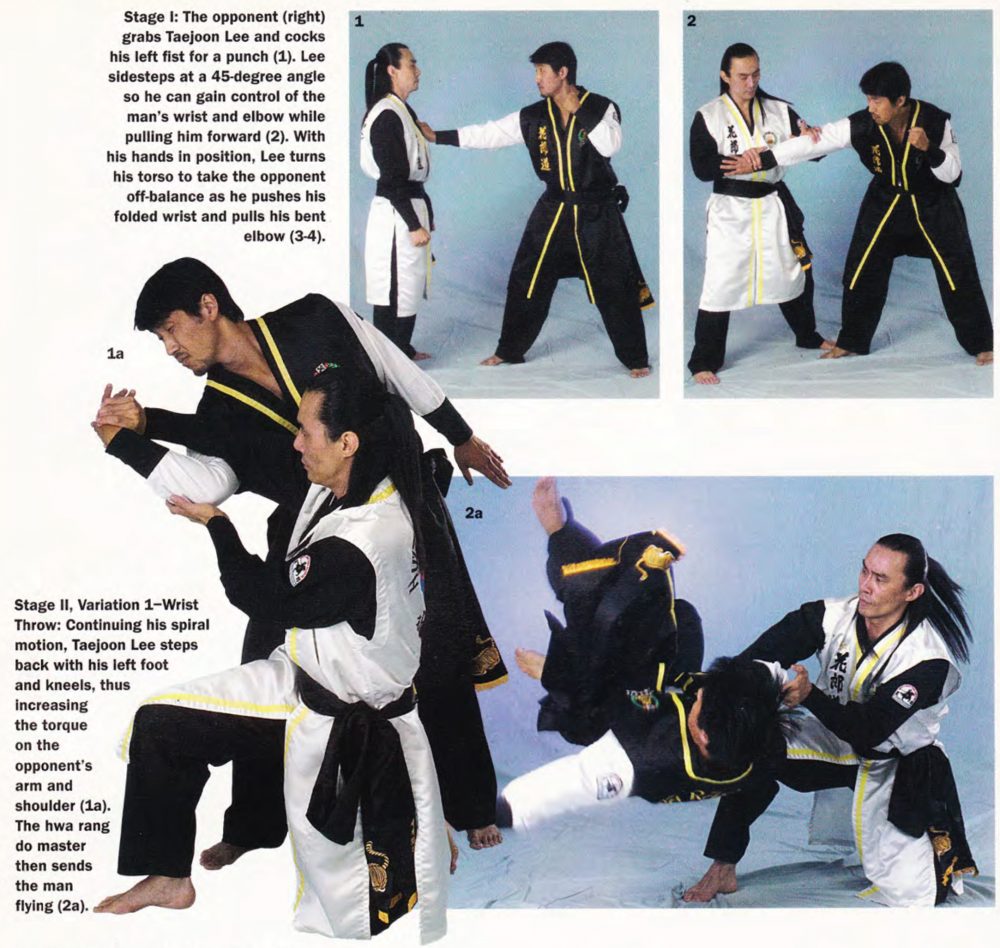

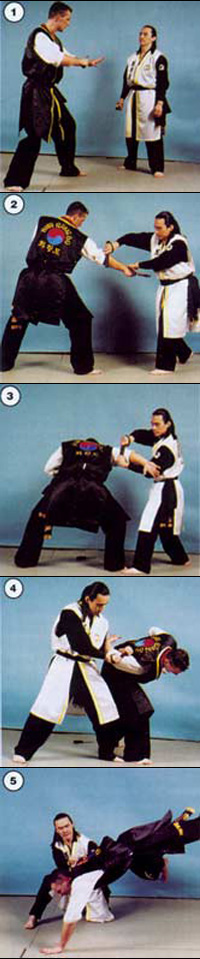

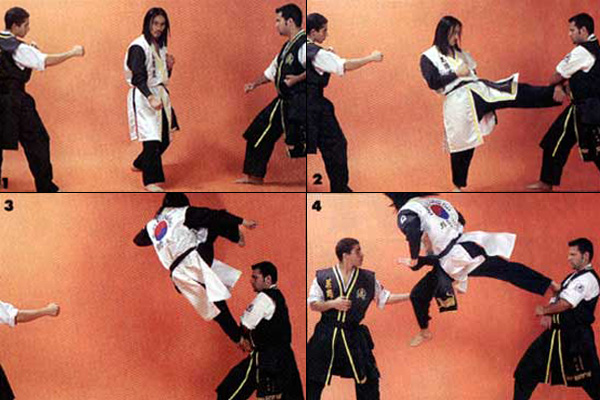

Stage I: Acquiring Grip and Angle

In this stage, one of your hands contains and pushes your opponent’s hand while the other pulls his elbow. The hand on his hand applies its force to the outside, while the one on his elbow applies its energy to the inside. With quick vibrational force, the shoulder can be dislocated. (The photos illustrate the application of this position against an attacker who’s pushing or grabbing the defender’s chest with one hand and preparing to strike with the other.)

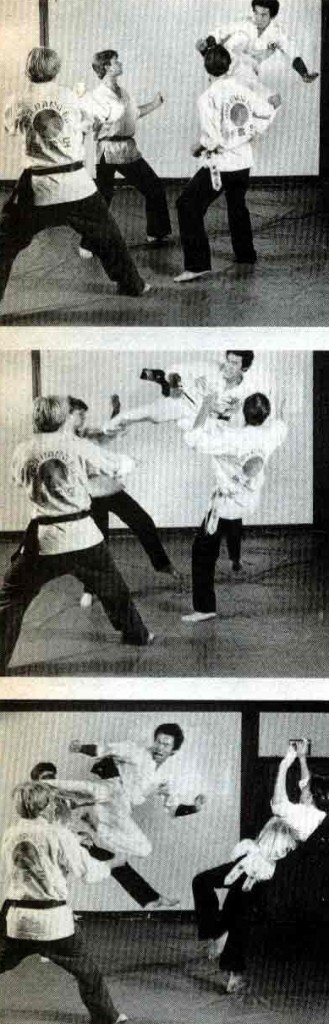

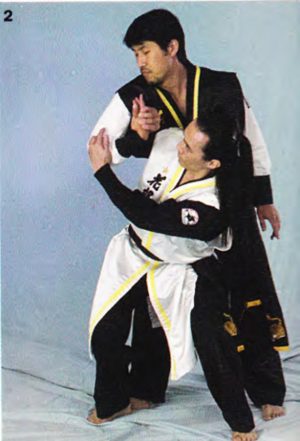

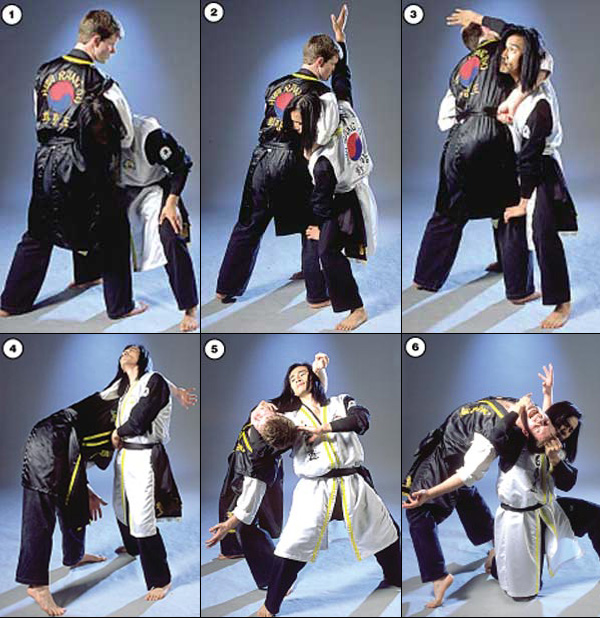

Stage II: Setups and Takedown

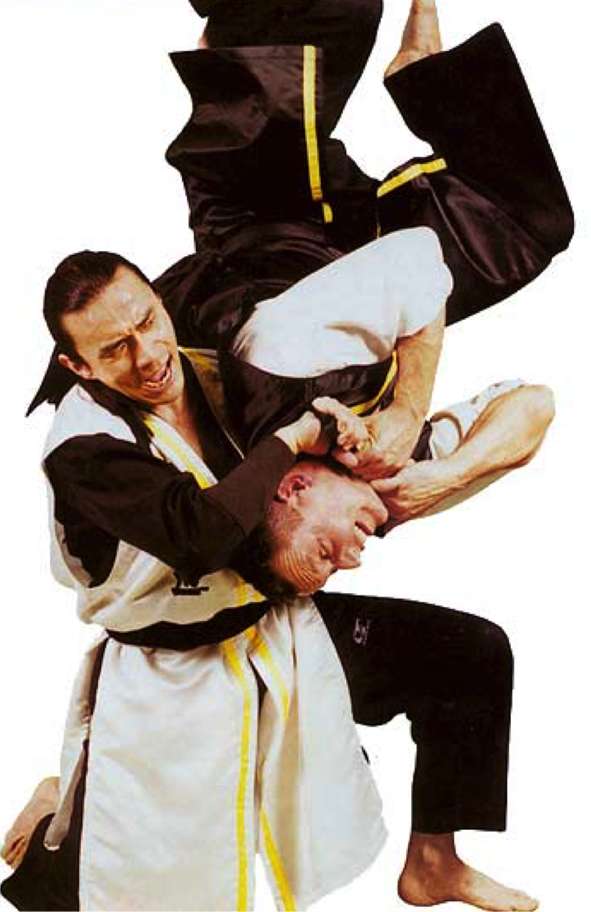

There are two main outcomes in Stage II: The opponent doesn’t react in time and gets thrown by the outward C-lock joint manipulation, or he resists and tries to avoid the outward rotation of his arm.

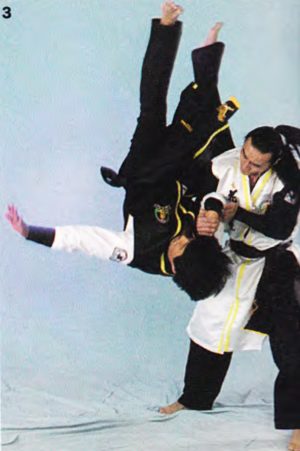

- Variation 1 – Wrist Throw: To apply this takedown, use the same principles as you did when executing the C-lock. Step through with the leg that’s on the same side as the hand you’re using to control your opponent’s hand. (In the photo sequence, it’s the right arm and the right leg. Notice how Lee drops to his knee to use his body weight to take down the opponent.) The most common mistake is trying to execute the takedown by swinging your arms laterally or downward. That increases the chance of losing the proper angles of control and manipulation on your opponent’s joints. Rotating and pivoting shouldn’t be emphasized because excessive lateral movement can open the angle of control. A direct, constant drive from your hand against his hand, along with a pulling counterforce on his elbow, is far more necessary for the takedown.

- Variation 2 – Spinning Shoulder Throw: The way it’s executed is similar to the basic shoulder throw. When the attacker tries to resist the outward rotation of his arm and shoulder, don’t fight the force with force. Instead, go with the attempted counter, drawing him into another takedown technique. “Why butt heads with someone who has his mind set on doing something?” Lee asks. “If he doesn’t want to allow his shoulder to be rotated outward and insists on rotating his shoulder inward, use his motion, his resistance to help you put him in another throw – which is a spinning shoulder throw, in this instance.” To explain the finer points of this move, Lee adds: “Instead of putting your shoulder into his armpit to execute the throw, place your right forearm under his triceps close to his armpit to create the leverage for the shoulder throw. Maintain the C-lock by keeping your right hand on his hand and your left hand pulling on his elbow. It is important to keep his right elbow elevated so he does not slip off to the side. If he does, however, this technique easily transitions back into a standard two-hand C-lock.”

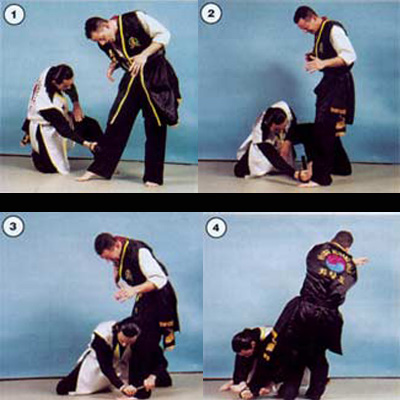

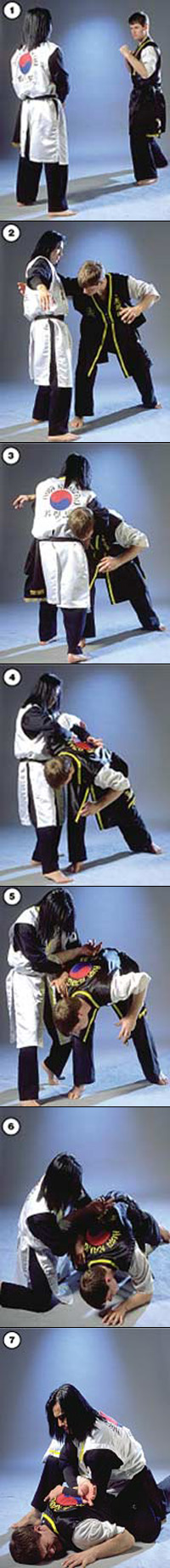

Stage III: Ground Control

Just as Lee teaches two options for taking the opponent down, he offers two variations for ending the conflict with a submission. The submissions vary with the placement of your right knee, which can be affected by the momentum of the throw.

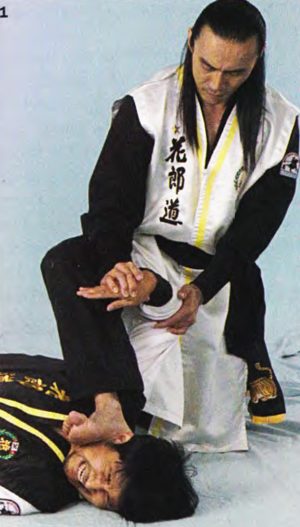

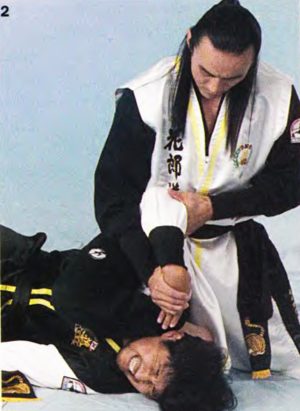

- Variation 1 – Outside Knee-on-Neck Wrist Quick Lock: This technique can be enough to immobilize or submit your opponent. However, it’s usually a transition move, suitable for use as a temporary hold or to transition into a tighter submission. Lee teaches five important points:

- Place your knee on the outside of your opponent’s neck. If he has his chin down and is facing straight up, apply pressure with your right hand on the point below his ear or under the jaw to gain compliance.

- Contain his elbow on the fold of your arm near your bicep ad press your body forward to pin the limb with your upper arm, thus preventing his escape.

- Cup your left hand over your right to ensure greater control.

- Don’t fall onto both knees as you drop. Rather, place only one knee on the ground, then bridge by pushing your hips forward and arching your back. Or sit up. Either option will put pressure on his wrist.

- Keep his right shoulder up. If he tries to turn toward you, this action will stop him. (This is another reason for placing your knee on the side of his neck.) If he tries to turn away from you, his shoulder position will enable you to apply greater tension on his wrist.

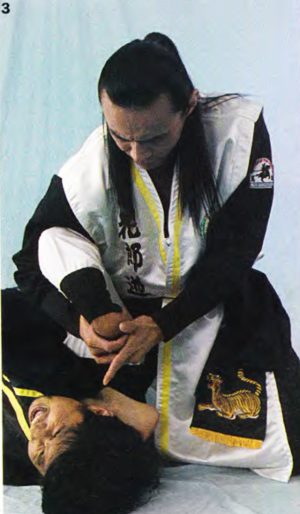

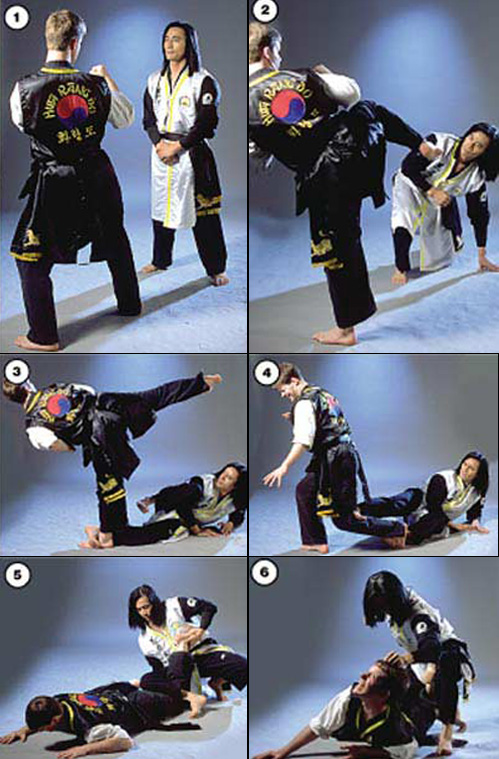

- Variation 2 – Inside Knee-on-Neck Wrist Quick Lock: This option allows you to place your leg over his shoulder by first stomping on the inside of his face, then slipping your foot under his neck. While the technique employs another quick lock on the wrist, it has a high probability of submission. That’s because placing your knee or shin on his throat creates panic. The upward pull of his bent wrist works with the downward pressure on his throat to amplify the pain in both locations.

Maximum Benefit

Lee says his three-stage method of training benefits everyone because it places both sides – the defender and the aggressor – at minimal risk while progressively familiarizing students with effective combat techniques. While many people are socialized to believe that striking another person is wrong, join-manipulating and grappling techniques don’t suffer from the same stigma. Indeed, with so much media coverage of cases that involve excessive use of force – often in the form of percussive techniques – this method seems logical and legally sound.

“Everyone knows about the effectiveness of grappling, but many people overlook standing grappling range, where joint manipulation is at its finest,” Lee says. “That’s one of Hwa Rang Do’s strong points. We train to handle aggressive opponents without having to resort to pummeling them into prime-time news. This also gives teachers, police and security personnel a way to regularly drill and internalize a set number of self-defense techniques in a systemize and progressive manner. Nobody has to be reduced to a victim or turned into a savage for lack of a politically correct self-defense system.”

Am-ja is the “way of darkness.” In this division, trickery, deception and cunning are the key elements of success. One must use whatever method, tool, or strategy is necessary to gain an advantage and defeat the enemy. In am-ja, the only honor lies in the ultimate outcome. Like the Machiavellian principles, the end justifies the means. In this school, one learns techniques in manipulating the enemy psychologically, physically and emotionally to confuse him, then move in for the final blow. In ancient Korea, the way of darkness was necessary for maintaining national security.

Am-ja is the “way of darkness.” In this division, trickery, deception and cunning are the key elements of success. One must use whatever method, tool, or strategy is necessary to gain an advantage and defeat the enemy. In am-ja, the only honor lies in the ultimate outcome. Like the Machiavellian principles, the end justifies the means. In this school, one learns techniques in manipulating the enemy psychologically, physically and emotionally to confuse him, then move in for the final blow. In ancient Korea, the way of darkness was necessary for maintaining national security.