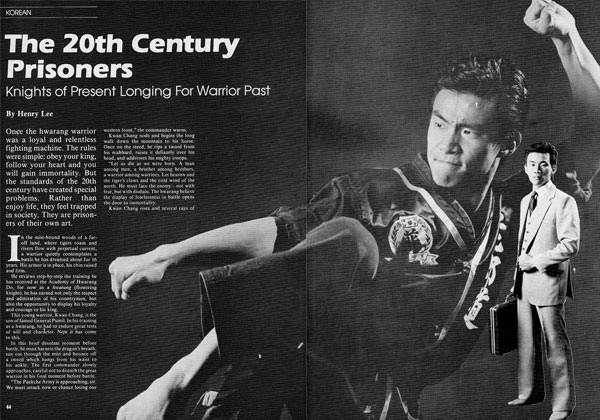

Once the hwarang knights were a loyal and relentless fighting machine. The rules were simple: obey your king, follow your heart and you will gain immortality. But the standards of the 20th century have created special problems. Rather than enjoy life, they feel trapped in society. They are prisoners of their own art.

In the mist-bound woods of a far-off land , where tigers roam and rivers flow with perpetual current, a warrior quietly contemplates a battle he has dreamed about for 16 years. His armor is in place, his chin raised and firm.

He reviews step-by-step the training he has received at the Academy of Hwa Rang Do, for now as a hwarang ( flowering knight). He has earned not only the respect and admiration of his countrymen, but also the opportunity to display his loyalty and courage to his king.

This young warrior, Kwan Chang, is the son of famed General Pumil. In his training as a hwarang, he had to endure great tests of will and character. Now it has come to this.

In this brief desolate moment before battle, he must harness the dragon’s breath, sun cut through the mist and bounce off a sword which hangs from his waist to his ankle. The first commander slowly approaches, careful not to disturb the great warrior in his final moment before battle.

“The Baekche Army is approaching, sir. We must attack now or chance losing our western front,” the commander warns.

Kwan Chang nods and begins the long walk down the mountain to his horse. Once on the steed, he rips a sword from his scabbard, raises it defiantly over his head, and adresses his mighty troops.

“Let us die as we were born. A man among men, a brother among brothers, a warrior among warriors. Let heaven and the tiger’s claws and the cold wind of the north. He must face the enemy – not with fear, but with disdain. The hwarang believe the display of fearlessness in battle opens the door to immortality.

Kwan Chang rises and several rays of earth be witness to our glorious triumph.”

With Chang in the lead, the army thunders across the open plain and into the heart of the Baekche Army. But the enemy is too great in both skill and number and Chang is captured.

Since his high-ranking battle crest indicates that of a general’s son, he is taken before the Baekche general. Lifting Kwan Changs war helmet, the Baekche general is shocked at the youth of the prisoner. Thinking of his own son, the Baekche general decides against execution and sends Chang back to the Silla lines.

“Go back to your father, young one. Go back in peace,” the general says in a fatherly tone.

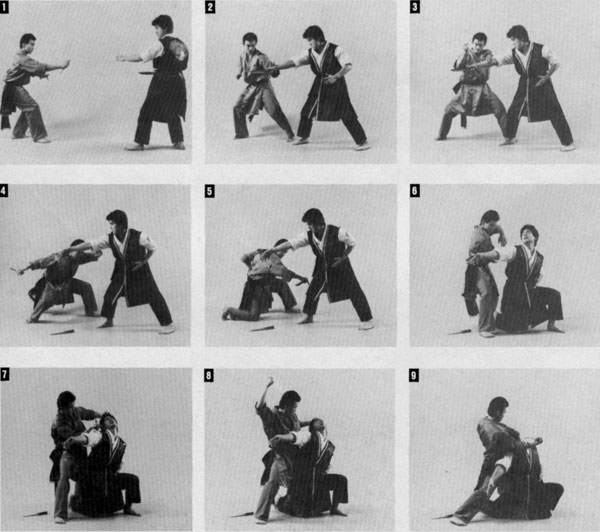

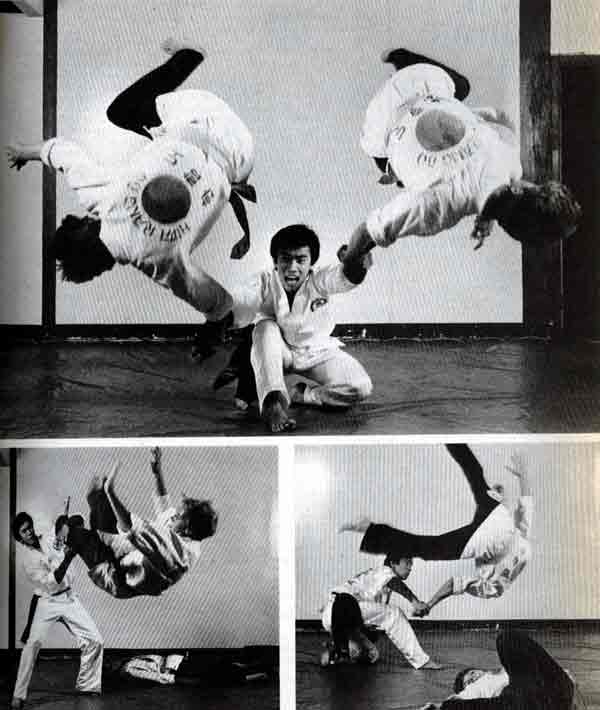

After returning to his father, Kwan Chang asks permission to return to the front. There is no answer; the question is moot. The young Chang takes a sip of water, mounts his horse and charges back into the fray. After a long day of fighting, Chang once again is captured. But after being disarmed, he breaks loose and kills two guards by hand. He then attacks the gerneral’s second in command. With deadly grace and speed, Chang spins 540 degrees in the air and delivers a killing heel kick into the general who sat on his horse, a full nine feet from the ground.

Finally subdued, he is taken before the Beakche general. Much distressed over the loss of his commander, the general says, “I gave you your life once because of your youth. But now you return to take the life of my best field commander. For this you will die.”

Kwan Chang closed his eyes, bent his head toward the earth and prepared for the end. “I may die,” he says to the general,”but through my death the spirit of the hwarang will live forever. Life is like a feather. Loyalty is like hard steel.”

Late that night, Chang’s head and horse returned to the Silla lines. General Pumil respectfully untied the head from the saddle and cleaned the blood which had been dripping from the severed veins.

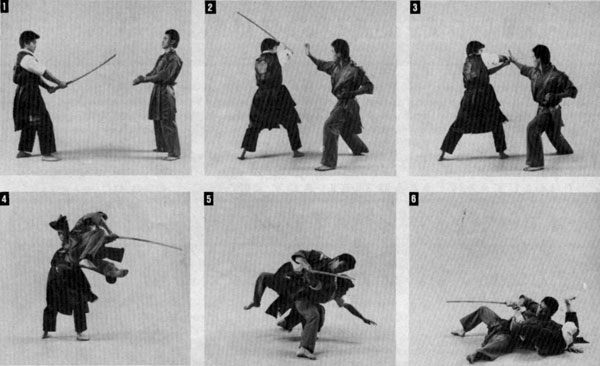

“My son’s face is as it was when he was alive,” he said, shouting to his men and holding the head for all to see. “He died in the service of the king. There is nothing to regret.” The king rode back into battle and eventually defeated the Baekche general. This legend became the basis for a hwarang do sword form.

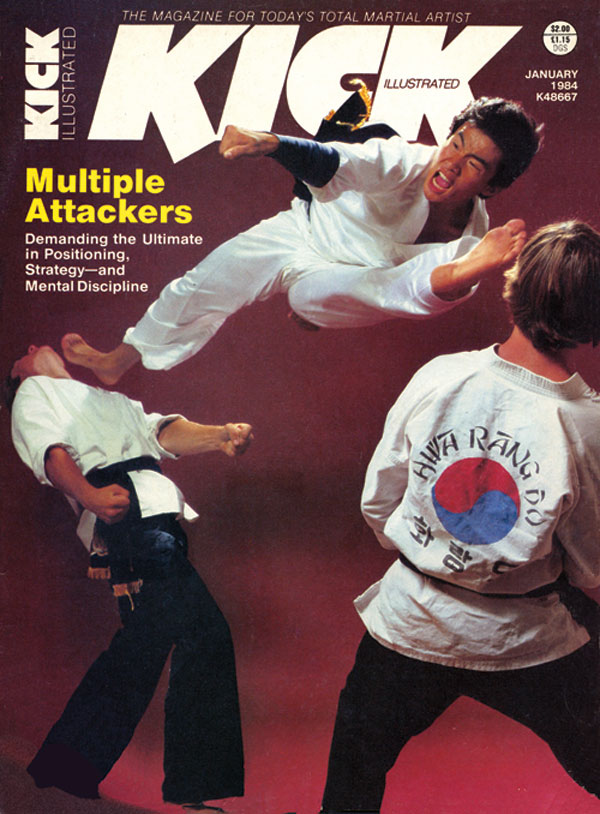

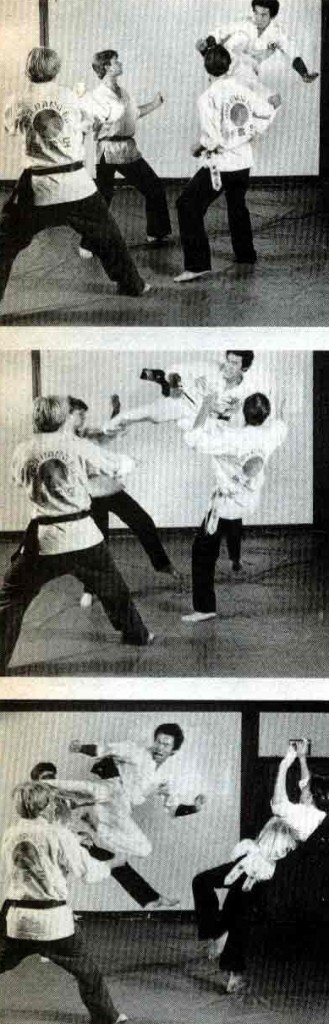

In the 20th century, where does the battlefield lie for the hwarang warrior? Where is the honor in dying for a country or an ideal? How does this dying breed of warrior survive in the concrete jungle where ethics and morality are forgotten concepts? There are wars and fueds among nations, but they are too politically contaminated by the needs of a few. Is there a war today that demands the human essence – his spirit, his honor, his loyalty? These warriors do not fight with M-16’s, .45-caliber pistols or submachine guns. Instead, they fight with the human spirit. They face their enemy with the extension of their soul, a sword, a bow, a knife – weapons which take skill to master. Tragically, the warrior is trapped in a society that deprives him of his dignity. People no longer respect and admire the warrior for his courage and bravery.

The warrior of this century must fight a new type of enemy – one who dresses in a three-piece suit, carries a leather briefcase, strives to expand his capital budget, and destroys his competitors with corporate takeovers. How does a warrior who only knows the blade and martial ethics of the Orient fight against this mighty foe? Are we to adopt his mode of attack and face him at the 20th floor of his corporate headquarters?

No. The hwarang wants to experience life, replete with its rewards and disappointments. Life – failing and succeeding, making mistakes, falling, erring – this is human and this is the greatest joy of a hwarang. He wants to help the seeds of mankind blossom into a beautiful flower, which is the epitome of perfection because it possesses natural beauty.

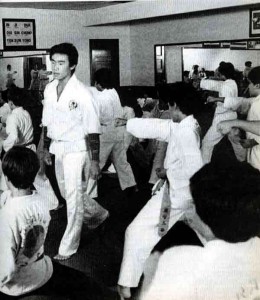

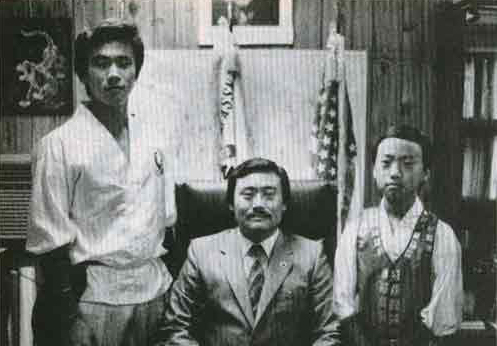

However admirable this golden concept, it is not practical in the 20th century. Martial arts teachers struggle to keep open their places of worship. They must compete both mentally and physically.

The hwarang’s ancestors never needed to pay rent for a training hall; never dealt with loan companies or the federal government; never were hit with lawsuits or had to pay liability insurance; and never paid college tuition.

Imagine a time when all people had to do was train their minds through meditation, their bodies through thousands of hours of techniques and their spirits through yogic concentration.

The mind is at the core of hwarang do training. The brain, practitioners say, is divided into four distinct quadrants. The first quadrant measures 0-90 degrees and signifies the range of human behavior. At the 90-180-degree level is a quadrant that covers the range of extraordinary human powers. The third quadrant, running from 180-270 degrees, includes the realm of supernatural powers. The final quadrant is in the category of Buddha, where the body becomes one with the universal ki (internal energy) and is transformed into pure spirit and vital force.

All humans possess the potential to enter the fourth quadrant, but how are we to get there when we can’t even concentrate our minds to exercise daily activities? How are we to overcome the stress and find enlightenment? Is the answer to ignore responsibilities to family and society and search for a hidden monastery in a remote corner of the world?

Maybe…

The conflicts and frustrations are many to a traditional warrior like the hwarang. Imagine you are a man who cannot see, hear or speak, but somehow has witnessed a great revelation. How can you tell others of this great news?

You can’t. And the hwarang feels the same frustration in his heart. Like the blind man, the hwarang is trapped by social convention. The ignorance of society blinds the eyes. Polluted noise deafens the ears. And foul language twists the tongue.

Today, the forgotten hwarang preside in hundreds of dojang (training halls) throughout the world. They are preparing for a battle that will someday set them as free as Kwan Chang was upon his death. The trials and tribulations of these warriors arise from their need to escape linear time and return to an age where knights and warlords ruled the world. They long to recapture the bliss of knowing life is being lived as it should. And that one is only confined by one’s imagination.