By Fernando Ceballos

Photos by Robert Reiff

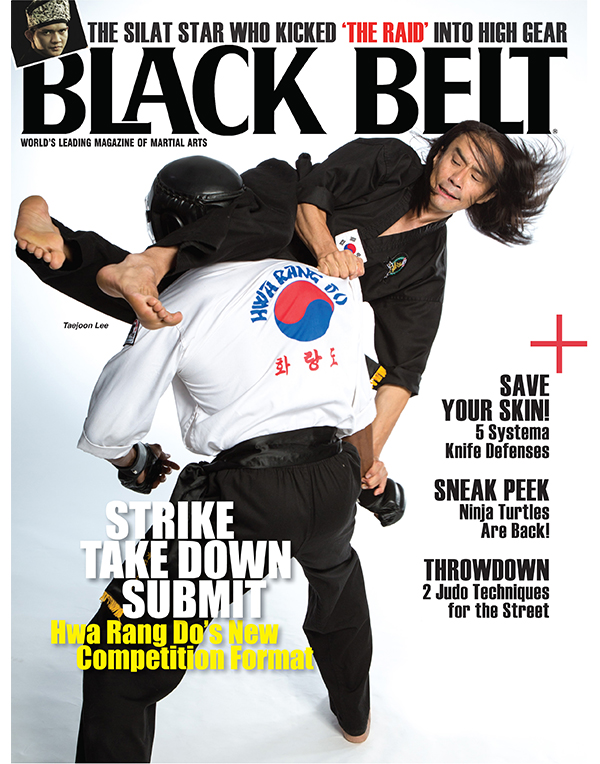

"New Form of Standup Competition is the Final Element Needed to Evaluate All-Around Martial Arts Skill!"

At first glance, you’d think you’re watching a Muay Thai match up. However, if you look closer at their equipment you’ll notice some key distinctions.

They have shin guards and black head gear, however the head gear itself has a face guard and padding on the top of the head. And the gloves are open finger gloves similar to MMA.

The fighters engage with lighting fast punching and kick-combos, including flying and spinning kicks followed by takedown attempts and throws.

They go to the ground frequently, but there is no long drawn out grappling stalemate. In fact, after a 5 count, the fighters are always brought to their feet if there is no successful submission victory.

We see a single leg takedown attempt, immediately followed by a leg lock and yell of “tap” within a second of hitting the mat. It happens so quickly, you look around for a replay monitor.

The fighters return to center ring, the referee gives the command to bow, raises the winner’s arm and brings the two combatants together for a hug. After some good sportsmanship, the two depart to calmly take their seats beside an open mat ring and the next two fighters are announced.

What is being described is one of the many martial sporting events, Yongtoogi (or Stand-Up & Submission Fighting), which takes place during 2 days of competition for the World Hwa Rang Do® Championships. Other events during the Championships include grappling, sword fighting, stick fighting, and other events comprising of over 10 categories of competition.

“This is our unique and the world’s only, decathlon of martial arts competition” Lee says – 8th Dan Hwa Rang Do Grandmaster and President of the World Hwa Rang Do® Association.

“Most martial artists spend months training for 1 fight or at most one tournament. Yet, over 40% of our competitors will compete in 10 tournaments, over the course of the two days, not only testing their skill in each category, but their endurance. Our advanced students compete in 1 additional tournament - Yongtoogi – our advanced submission fighting category, designed to condition fighters to master Hwa Rang Do’s Self-Defense formula – Defend, Takedown, Quick Submit”.

Lee observes all matches from behind the time keeper’s table, with a stoic expression on his face. Only smiling and clapping, along with the audience when the match finishes, acknowledging BOTH combatants for their efforts, displaying no favoritism.

What is most striking about the end of all matches, is how calm the winning fighters are after each match. None of them raise their own hands, gloat and celebrate after their victory – regardless of how difficult or dominant they performed.

The fighters’ mutual respect for one another clearly overrides any desire for an understandable emotional outburst, which follows most martial arts victories we may see on television or other live sporting events.

Yongtoogi and the rest of Hwa Rang Do’s tournament categories are held within a “closed tournament” format – meaning no groups without a direct affiliation to the World Hwa Rang Do Association (or WHRDA) may enter any of the tournaments.

“We’ve pretty much kept this format a secret, and have only recently held these events in public places, such as at the Origins International Martial Arts Festivals at Disneyland in 2011 and 2012. Those events were the first time, we allowed the rest of the martial arts community and general public to see what we have.”

A Brief History of Tournaments in 70’s & 80’s

It has been almost 25 years since Hwa Rang Do participated in any open tournaments – whether organized by the WHRDA or other martial arts groups.

“Before developing this decathlon of tournament categories we have today, like other martial arts groups, we previously participated in competitions all over the country and the world, dating back to the mid-70’s.”

In the 70’s, Kenpo and Karate groups hosted stand-up fighting tournaments, each with their own rules. There was no protective gear and the rules were similar to what we all saw in the film, ‘The Karate Kid’ – one hit, one point.

Some of the Kenpo organizations allowed groin strikes. None allowed takedowns, except Karate but only in the form of a leg sweep, however no points were awarded for sweeps.

Rotational kicks were also not allowed, which posed a problem for Hwa Rang Do and other dynamic fighting arts.

“We couldn’t fully express the comprehensive nature of our art. We would be disqualified if we attempted a spinning kick or takedown, but since we were a small group at the time, we wanted to show the martial arts community that even with these limitations, we could still win and we did win – a lot.”

As described in Black Belt Publication’s new book, ‘The Complete Michael D. Echanis Collection’ book, these frustrations were even apparent when military combatives legend, Michael Echanis, who was studying Hwa Ran Do under it’s founder, Joo Bang Lee, would storm into tournaments and challenge the champion to a street fight, most of the time leaving the champion bloodied and unconscious.

“My father certainly did not condone or endorse Michael’s actions, which is why he encouraged him to go back to military and teach the Special Forces. He was a warrior, born for combat and he was better suited for the military, not civilian life. However, the statement he was trying to make was clear. We have an art which cannot be fully expressed in, what at the time, were contemporary martial arts competitions.”

According to Lee, eventually Hwa Rang Do began running their own “open tournaments” organized by his father Joo Bang Lee, but they stuck to common rules, in order to attract outside groups. While they were very successful, the tournaments were a challenge to coordinate and appeasing all groups and their requests for rules changes and special treatment was not easy.

In the early 80’s the politics of running tournaments became more than Joo Bang Lee wanted to take on and Hwarangdo ceased running tournaments for 4 years and chose to simply participate in open tournaments hosted by other groups.

“The benefit of participating in tournaments & demonstrations were obvious. It was a marketing tool and a way to allow our students to test their skills and overcome fear through the experience of competition. When we performed in tournaments, other martial artists and those in attendance wanted to join our organization. That allowed what at the time was a little known art called Hwarangdo to grow!”

When Taejoon Lee, entered college at the University of Southern California in the mid- 1980’s – already recognized then as a “master” rank – he had opened clubs not only at USC, but his group spread to UCLA, UC Riverside, UC Irvine, UC San Diego, Arizona State and others. News of these clubs spread and within a couple years, Lee literally led an army of college-age practitioners in the art of Hwarangdo.

He asked his father permission to run inter-school closed tournaments and eventually received his blessing to once again hold 2 open tournaments per year under the name of ‘BIG MAC’ – “Martial Arts Championships (MAC)”.

They did this in partnership with NASKA, the North American Sport Karate Association, whose rules allowed fighters to get points for takedowns, which was important for Hwarangdo practitioners, giving them more freedom to express their skills.

Hwarangdo practitioners competed in BIG MAC, in addition to outside open tournaments through the 80’s. However, once again, the challenges of working with outside groups became a problem, but this time, it was far worse.

Lee states that, “Tournaments became increasingly unruly with a loss of respect for each other and poor sportsmanship, which severely diminished the value of participating. Etiquette and respect for one another is a core part of our martial way, so clearly this was a problem.”

Lee recalls two incidents in particular, which ‘broke the camel's back’.

“There was one incident, I recall, where a competitor didn’t like a referee’s ruling, punched him in the face and a melee ensued. A few weeks later, at another event, 2 opposing teams were fighting on a stage at the Team Fighting finals and spectators started throwing chairs across the stage at each other.

“We started losing students because of negative experiences. As a result, we reduced our participation by sending only select students as representatives and then stopped completely by the early 1990’s.”

Developing the World’s First Martial Arts Decathlon

Lee and his father, Joo Bang Lee, decided that developing their own tournament format exclusively for Hwarangdo, which also reflected the comprehensive nature of the art, was the best course of action.

Adding to the Point Fighting, Open-Hand and Weapon Forms competitions, which were already in place, Lee first implemented a Gotoogi (or Submission Grappling) program adapted from self-defense techniques in Hwa Rang Do, with no striking for the purposes of competition. You could only win by submission or points, similar to Jiu Jitsu or Catch Wrestling.

Then came the development of the ‘mugidaeryun’ or weapon fighting categories, which began as Kumdo, Korea’s counterpart to Japanese Kendo.

As documented in the article of January 2014 issue of Black Belt Magazine, ‘Hwa Rang Do Weapons: Taejoon Lee and the Korean Martial Art’s New Spin on Traditional Sword and Stick Fighting”, Lee developed & patented a leg attachment to the traditional Kendo armor called the “Hache Hogu” or leg protector, which opened the category up to allow for strikes to the leg and spinning attacks, creating a new dynamic weapon fighting sport - Gumtoogi (Sword Fighting) and Bongtoogi (Stick Fighting).

Expanding the competitive categories further, the same armor was used for long sword, twin short swords, long staff, twin stick fighting and mixed weapon fighting competition as well.

By the late 2000’s, Hwarangdo’s World Championships had evolved from a simple half-day 3-category event consisting of forms and point fighting, into a 2-Day 10-category martial arts decathlon.

During this period, the advent of MMA had also simultaneously transformed the martial arts world, with a greater emphasis on ‘reality based’ competition.

It is said that MMA is “as real as it gets”, however that too would prove to be far from what would take place in a street fight or self-defense situation, yet there was clearly an interest in what a martial art like Hwarangdo could do in a full-contact format.

“Even back in the 80’s, my father had deep philosophical conflicts, about having our students engage in full contact fighting, yet always knew that competition would eventually evolve to what we’ve come to know today as MMA.

“However, being who we are, we had to think more deeply about what we wanted to represent. Our art transformed the early days of empty hand and armed combatives in the Special Forces through Michael Echanis. We were dominant in the late 70’s and 80’s in sparring and forms competitions. And we now run the world’s only 2-day martial arts decathlon. From a self-defense and combat sport perspective, we’ve had nothing to prove and since the 1990’s, we’ve only gotten better.

“In the past, there have been students of ours whom wanted to compete in full-contact tournaments outside our organization. We could not allow it while they were affiliated with our association, so in those cases, we mutually agreed to part ways so they could pursue their goals and they performed extremely well. However, we asked that they not claim having trained in Hwa Rang Do nor did we want credit nor did we support them. It wasn’t what we were about.”

“Our priority has always been maintaining that which is unique to us – our sense of brotherhood, our family bond, the spiritual component, our hwarang heritage and respect to our higher ranks and masters.”

In the late 1990’s & early 2000’s, Hwarangdo did in fact develop a full-contact sport category, “Kyuktoogi” with only advanced students & those demonstrating a strong mental maturity allowed to train and compete in. However, Lee was not yet comfortable with the social dynamics it created.

“In Full Contact Fighting, the goal is to hurt or incapacitate your opponent. How does a group or organization who thrives on our bond and brotherhood, operate like a family, while having the goal of hurting each other, inside the ring?”

“We also wanted to maintain our leadership hierarchy. In sport, that is broken. The champion and contender rankings is what dictates the hierarchy, however just because you are a champion, does not make you a leader, nor does it make you wise nor a good person. What we wish to cultivate are leaders, not just fighters.”

“That’s not to say we didn’t want to create a ‘reality based’ fighting format, but it had to align with our values and goals.

“First, it had to promote the altruistic ideal of competition, which is to push one another and test the skill of our brother or sister across the ring from us. Second, the rules had to promote the development of a valuable skill set which could be potentially life saving, if mastered.”

Hwarangdo’s Fight Plan – Defend, Takedown, Submit

The answer came when Lee authored ‘Hwa Rang Do: Defend Takedown Submit”, published by Black Belt, which outlined the art’s self-defense strategy, which could be adapted for military, law enforcement or personal self-defense.

The strategy is broke down into 3 components:

Defend – Using distancing and striking techniques to defend and setup the next stage of the formula…

Takedown – Engage in a lock or hold, which will neutralize your opponents striking by taking them to the ground, then…

Quick Submit – While maintaining a dominant top position on the ground, quickly apply a lock-up to either, submit your opponent, choke them out or inflict more serious injury through a bone break or dislocation, should they not submit or pass out.

The important thing to know is that Hwa Rang Do emphasizes the “quick submit” strategy – meaning to quickly recognize the lock-up opportunity present and immediately execute the most effective finishing technique to dispose of an opponent, while avoiding a BJJ style ‘roll’ on asphalt or concrete, which leaves one vulnerable to injury and multiple attackers.

The dominant top position also allows the Hwa Rang Do fighter to quickly recover and react to other threats.

This formula is what the ‘Yongtoogi’ sport became based on. Rather than encouraging Hwa Rang Do competitors to go for the ‘knock out’, Lee wanted them to focus their efforts on mastering the ‘quick submit’ and showcasing the full breadth of the art.

The matches would entail two continuous minutes of fighting. The striking would be limited to medium force attacks to the head and body, to prevent unnecessary injury while at the same time encouraging them to fully express the striking and takedowns available in Hwa Rang Do’s vast curriculum and to setup for a ‘quick submission’. However, a fighter would have only 5 seconds to submit their opponent, before they are stood up by the referee and the match is allowed to continue.

Should a competitor successfully apply a submission and get the other person to ‘tap out’, the match would be over and he or she would be declared the winner.

Should the match go the full 2 minutes, 3 judges would score the bout for each fighter on a scale from 1 – 10, in the areas of “striking”, “takedowns” and “spirit”. Each judge would add up their score and choose a winner.

The fighter with 2 judges scoring in their favor would win the match.

The “spirit” category is left up to the judge’s discretion to award a fighter credit for things not covered in the other two categories, such as energy level, difficulty of techniques performed and aggressiveness.

Now, five seconds on the ground may seem like a very short period of time, but that is precisely what Lee wanted. He wants to train his practitioners to quickly recognize the available finishes and apply them without hesitation and with precision.

This experiment has proven fruitful in the past 2 years that these rules have been in place for Hwa Rang Do, with matches resulting in tap outs via armbar, shoulder locks, ankle locks in addition to many decisions.

Lee says “My goal is not really intended to create champion fighters, although that certainly is fun to watch and an excellent test of skill for our students via competition. My goal is to help my students develop the self-defense skills against each other, which could one day save their lives, without the ego-driven culture of full contact fighting gyms and most importantly, preserving our martial way – our traditions, respect for your senior ranks, respect for one another and our familial bond.”

Videos

Seminar

Competition