Choong 충 - Loyalty “The True Meaning of Martial Art”

Published in Budo International November 2018 Issue

By: Grandmaster Taejoon Lee

Part 1 – The Story

In 660, during the Three Kingdoms Period in Korean History, the kingdom of Baekje on the western border fell to the Hwarang Warriors of the Silla Kingdom who made an alliance with the Tang Empire (China). Soon after, the kingdom of Goguryeo, the largest of the three kingdoms to the north, also fell in 668 to the Silla-Tang Alliance, which completed the unification of the Korean Peninsula for the first time. The Unification Wars were led by the Hwarang Knight, General Yushin Kim, and his successful campaign elevated his reputation to legendary status as the greatest general of the Silla Kingdom and one of the most important figures in Korean History.

This is a heroic tragedy, mythical in nature yet a true Hwarang story of the second son of General Yushin Kim, Wonsul Kim. He was an accomplished Hwarang Warrior who also became a general like his father. After the successful unification of the Three Kingdoms under the Silla banner, now Unified Silla, the Tang Empire betrayed the Silla Kingdom, aiming to conquer what General Yushin Kim worked his entire life to achieve, aiming to subjugate the Silla Kingdom as a territory under the Tang Empire. General Wonsul was near Baeksu Castle in August of the year 672, fighting the Tang Army. The Hwarang Warriors of Silla seemed to have been winning the battle in the beginning and anticipating an imminent victory, the generals decided to disperse the regiment. The Tangs (Chinese) decided to take advantage and attacked with full force. The Silla Army took heavy casualties with countless soldiers killed as well as several of the other Hwarang Generals.

Realizing defeat was unavoidable, Wonsul prepared to die by charging into the enemy lines. His executive officer, Tamnung, held him back and said, "It is not difficult for a heroic man to die, but it is difficult to choose the proper time. It is better to make plans in life for future success than to die without having any victory."

Wonsul answered, "A Hwarang cannot retreat in battle and die as a coward. Besides, I would be too ashamed to face my father." This is the Fourth Code of the Hwarang O Kae (The Five Codes of the Hwarang): “Im Jeon Mu Twae - Never to retreat in the face the enemy.” It also meant that if you go to battle, either you win, returning in victory or you die in battle, never to return.”

The Hwarang O Kae

SA GUN E CHOONG – Loyalty to one’s King and Country

SA CHIN E HYO – Loyalty to one’s parents and teachers

KYO WOO E SHIN – Trust and brotherhood among friends

IM JEON MU TWAE – Courage never to retreat in the face of the enemy

SAL SENG YOO TECH – Justice never to take a life without a cause

Wonsul whipped his horse to make a dash for the frontlines, but Tamnung seized the reins of his horse and did not let him go despite Wonsul’s resistance. As a result, Wonsul did not die at the battle and reluctantly, set off with the Supreme Commander to return to Gyeongju, the Capital City of the Silla Kingdom to face his father and the king. However, they were in hot pursuit by the Tang Army, who were gaining on them. The Chief Inspector, Taegam, stepped up and said to the Supreme Commander, “Strengthen yourselves and depart quickly. I am already 70 years old. How much longer can I live? Today will be the day of my death.” Then, he charged fearlessly into the enemy ranks, swinging his halberd, taking out many of the Tang soldiers, but outnumbered he was eventually killed. Seeing this, his son also charged and fell to his death.

Taegam’s sacrifice was not in vain as it gave the Supreme Commander, Wonsul and the troops the critical time needed to escape to safety. By taking hidden routes, they were successful in returning back home to the Capital, Gyeongju. When the great King Munmu heard what had happened, he asked his General Yushin Kim, who was also a good friend and confidant to the king, “Why is it that our army has suffered such a devastating defeat?”

General Kim answered, “The plans of the Tang (Chinese) are inscrutably devious. We should send troops to watch over strategic positions. Wonsul, however, has not only dishonored the charge of Your Majesty, but also neglected the instructions, which were given to him at home. He should be beheaded."

The Great King said, "In this campaign he was only the Adjutant General, Wonsul, cannot alone be punished so severely and if I were to behead him, then all the other commanders must be beheaded," and thus the King pardoned him.

General Kim replied, “I disagree, but you are the King so I shall abide. However, I am Wonsul’s father and as his father, I disown him. From this day forward I have no second son as a Hwarang would never return from battle defeated. Thus, he is dead to me.” Wonsul was ashamed and left with dishonor in tears. Fearing his father, he dared not appear before him and hid himself in the countryside.

In June 673, people witnessed several dozen crying soldiers in armor with weapons in their hands walking out of General Yushin Kim’s home. Then suddenly, they vanished without a trace. Rumors spread of this strange incident until it finally reached General Kim’s ears. He said, “They were the heavenly guardian soldiers who protected me. Now, my luck has run out. I shall die very soon." On July 1, 673, General Yushin Kim died of natural causes at an old age of 79, after spending more than two-thirds of his life fighting on the battlefield for his King and Country.

Wonsul returned home to attend his father's funeral. However, his mother, Lady Jiso, rejected him even though he was wrongfully accused of being a coward. She said, "For women there are three rules of obedience. Now, that I am a widow it is proper that I should obey my son. But since, a man like Wonsul could not be the son of his father, how could I be his mother?"

Wonsul was devastated and wept, beating his chest in agony, and would not leave. No matter how much he persisted, the mother, Lady Jiso, would not see him. With a deep sigh of anguish, Wonsul cried out, "How cruel is Heaven that I should suffer more by living than dying. I should not have allowed Tamnung to stop me. It would have been better to die than to live in shame and dishonor." Then he retreated deep into the forest of Taebaek Mountain.

In September 675, once again the Tangs invaded with an army of over 40,000 (according to some Korean sources, it is said that the Tang’s army was actually about 200,000) led by the Tang General Li Jinxing. Wonsul came out of seclusion, returning once again to fight against the Invading Tangs with a Silla Hwarang Army of only about 30,000 at the Battle of Maseo. General Wonsul fought fearlessly as if anxious to die on the battlefield. However, he would not die; although he entered battle once more so that he may redeem himself with an honorable death that he was previously cheated from by dying in battle, once again it would elude him. He was invincible and no matter how hard he tried to die, he could not be killed. As a result, he achieved a great victory over the Tang troops and saved the Silla Kingdom from ruin. Lastly, a victory at the Yellow Sea by the Silla navy against the famous Tang General Xue Rengui secured the Unified Silla Kingdom against the Tang Invasion.

When the war was over, Wonsul was scheduled to be highly awarded with a hero’s welcome in Gyeongju, the Capital of Silla. However, Wonsul never returned to Gyeongju, but rather went deep into the mountains regretting his impiety to his parents.

Wonsul Kim spent the rest of his days in the mountains, never to be seen or heard from again, and died alone in an unknown year, at an unknown place, at an unknown age.

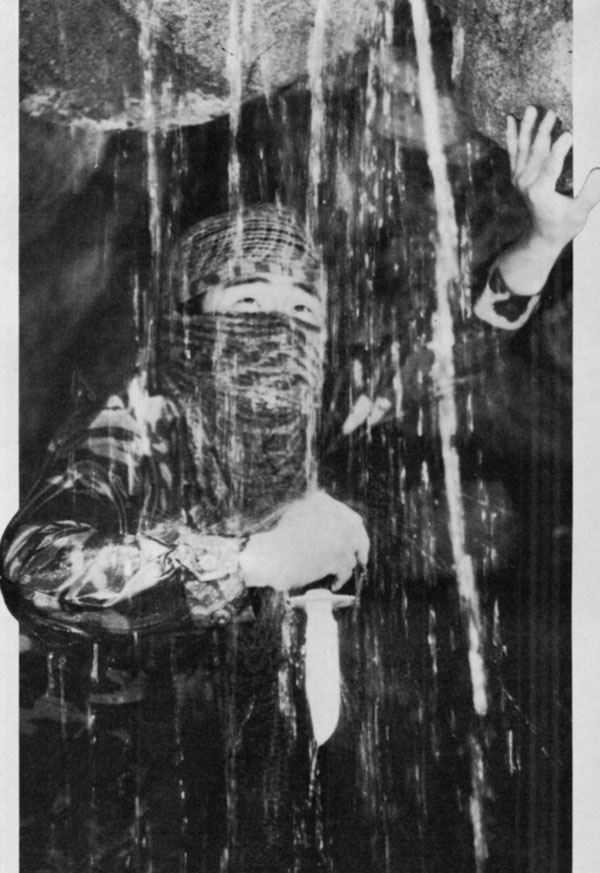

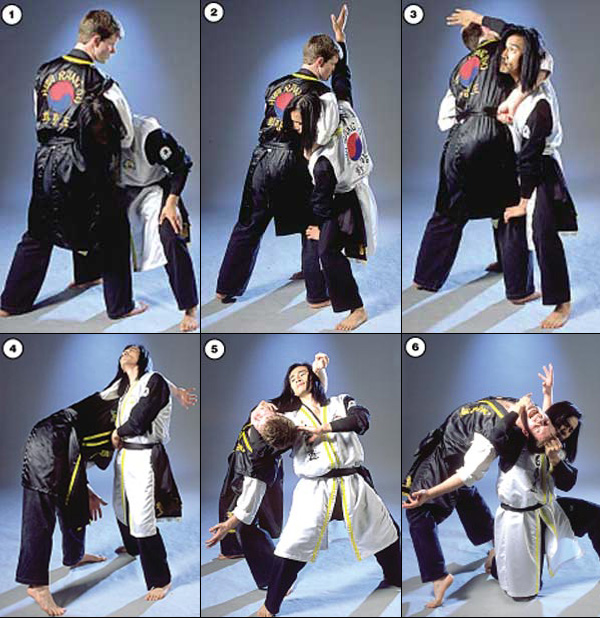

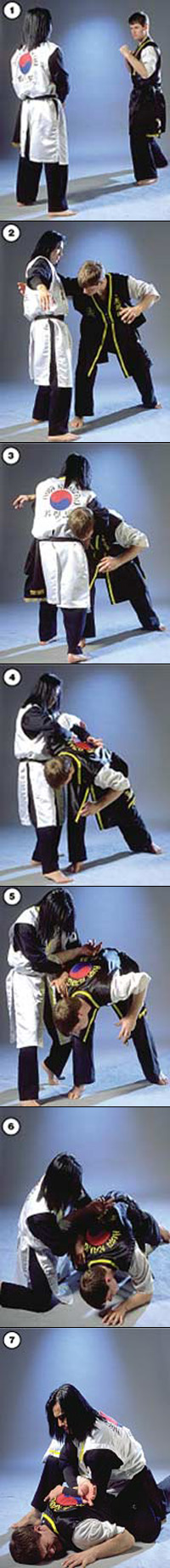

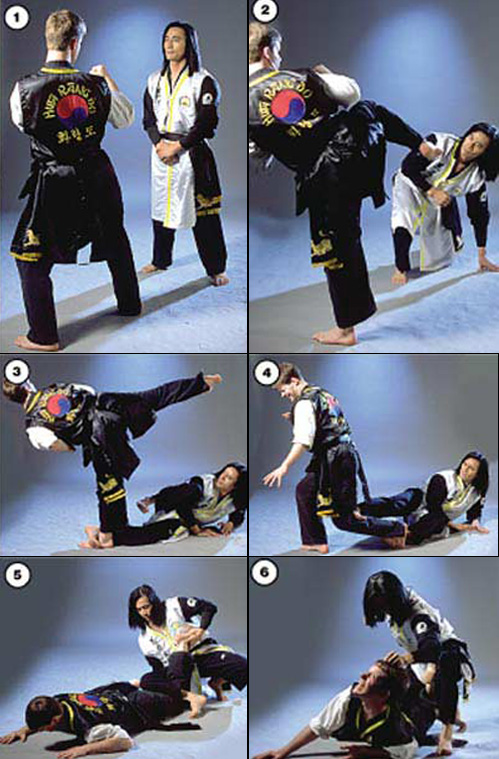

Am-ja is the “way of darkness.” In this division, trickery, deception and cunning are the key elements of success. One must use whatever method, tool, or strategy is necessary to gain an advantage and defeat the enemy. In am-ja, the only honor lies in the ultimate outcome. Like the Machiavellian principles, the end justifies the means. In this school, one learns techniques in manipulating the enemy psychologically, physically and emotionally to confuse him, then move in for the final blow. In ancient Korea, the way of darkness was necessary for maintaining national security.

Am-ja is the “way of darkness.” In this division, trickery, deception and cunning are the key elements of success. One must use whatever method, tool, or strategy is necessary to gain an advantage and defeat the enemy. In am-ja, the only honor lies in the ultimate outcome. Like the Machiavellian principles, the end justifies the means. In this school, one learns techniques in manipulating the enemy psychologically, physically and emotionally to confuse him, then move in for the final blow. In ancient Korea, the way of darkness was necessary for maintaining national security.